Development of Hostile Architecture

Hostile Architecture has been around since at least the 1500s when religious establishments commissioned spikes to be placed on ledges and window sills to prevent birds from perching. Over the centuries, this type of architecture has been used to impose social control and to limit public activities, most notably in government buildings, religious sites such as churches and temples, and other privately owned spaces. The modern conception of hostile architecture has gained attention in the 21st century, particularly in public spaces such as parks, malls, and other areas frequented by pedestrians.

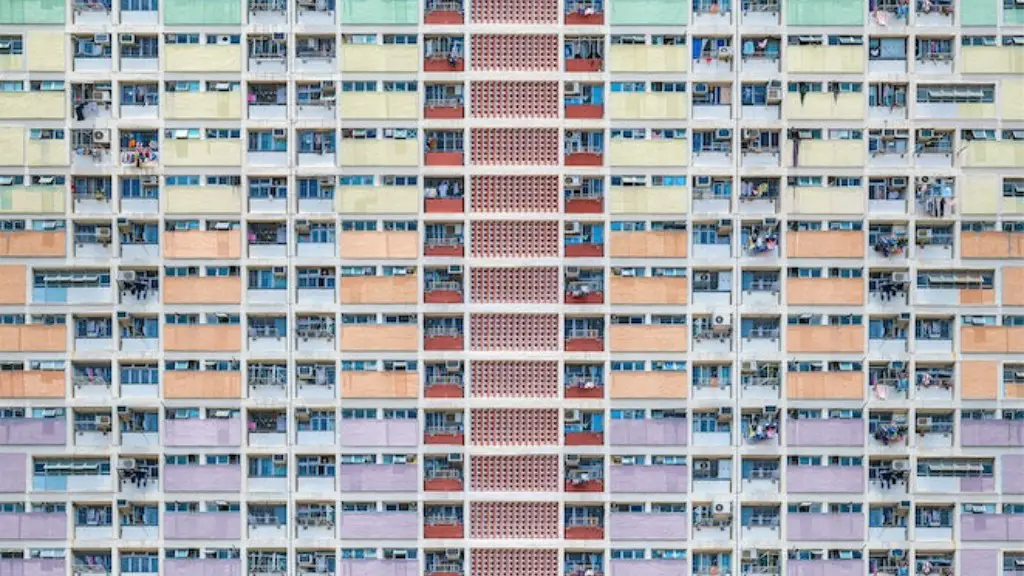

Hostile Architecture designates a type of architecture which aims to prevent people from using a space in a way unintended by the architects. Typically, Hostile Architecture involves the use of physical or spatial design features or materials which discourage or prevent people from engaging in activities such as sitting, loitering, or sleeping. Such features might include ridged or curved seating surfaces, raised armrests between benches, or surfaces that prevent people from comfortable lying down. This type of architecture has been dubbed variously as “anti-homeless architecture,” “defensive architecture,” or “hostile urban furniture.”

Uses of Hostile Architecture

Hostile architecture is a tool which has been used by public organizations, private businesses, and other entities to deter unwanted public behavior such as loitering, vandalism, or other activities seen as disruptive or unsafe. Such entities might include, for example, shops and malls, churches, schools, and public parks. Hostile architecture is also used as a tool to manage the flow of people within a space and direct the public to purchase or participate in certain activities rather than others.

The use of architectural features or materials to impose social control can be traced back to ancient times, though the modern formulation of Hostile Architecture has grown in popularity in the 21st century. As public spaces become increasingly commercialized and experienced as private spaces, hostile architecture has been adopted as a tool to manage public behavior in areas such as parking lots, plazas, and malls.

Criticisms of Hostile Architecture

While Hostile Architecture has been marketed as a way to deter criminal activity, the effectiveness of this type of architecture in preventing crime is highly debated. Critics of Hostile Architecture argue that the design elements used to discourage certain activities can also be used to prevent people from engaging in activities that are not only harmless, but also important for public welfare, such as providing seating for elderly individuals or places to rest and reflect. Experts have also expressed concern that the use of Hostile Architecture can deter vulnerable groups such as the homeless from accessing vital resources.

Other critics contend that hostile architecture further reinforces existing power dynamics and inequalities in public spaces. Designers are heavily biased towards a certain “ideal” user and implicitly condone the exclusion of those deemed “undesirable” or “dangerous”, including people of color, homeless individuals, and youth. Such exclusionary practices violate basic human rights and legitimize the targeting of vulnerable groups in public spaces.

Alternatives to Hostile Architecture

Rather than relying on hostile design elements or materials, many experts suggest utilizing a harm reduction approach to address public safety concerns. This approach encourages the establishment of positive relationships between the community, businesses, and authorities in order to identify and address sources of potential problems before they occur. Such preventive measures could involve addressing social, economic, and environmental issues in public spaces, as well as creating policies that target only specific types of behaviors.

Designers have also suggested incorporating public art projects in public spaces as an alternative to Hostile Architecture. Such projects have the potential to bring people together, foster a sense of community, and create meaningful public spaces. In addition, art can be used to tell stories that break down boundaries that separate communities and create more inclusive, equitable, and open public spaces.

Social Implications of Hostile Architecture

The rise of hostile architecture can have severe social implications. By limiting people from accessing public spaces and engaging in basic activities, such practices can lead to feelings of alienation, resentment, and exclusion. Hostile architecture can also reinforce existing power dynamics in public spaces and deter vulnerable populations from accessing resources and services.

Furthermore, the use of hostile architecture to deter people from engaging in activities deemed irresponsible or inappropriate can act to legitimize the targeting of certain individuals or groups. Such practices send the message that certain activities or populations are not welcome in public spaces, thereby reinforcing existing inequalities.

Impact of Hostile Architecture on Public Health

The impact of hostile architecture on public health is of particular concern. Studies have shown that access to public spaces is associated with improved physical and mental health outcomes; it can reduce stress levels, improve physical activity, and promote healthy relationships and social interaction. By reducing access to these spaces, hostile architecture can have serious consequences for public health.

Furthermore, hostile architecture can deter people from accessing vital resources and services, such as health care, housing, and employment. People who are without a home or those who are experiencing homelessness may be denied access to basic services due to the presence of hostile architecture, leading to further health complications.

Hostile Architecture in Political Spaces

Hostile architecture is often used as a tool of political control, particularly in authoritarian regimes. Construction projects, such as walls, fences, and barricades, are used to separate political opponents or subvert public protests. Such projects are often funded and managed by authorities, taking advantage of vulnerable populations in the name of national security.

For example, in 2013 the Russian government erected a towering wall around Red Square in Moscow, an area heavily associated with political dissent and protest. The wall was designed to prevent people from accessing the square, while also sending a message to those who oppose the government.

Legality of Hostile Architecture

The legality of hostile architecture is highly contested. While laws in some countries restrict the use of hostile design elements or materials in public spaces, others do not. In some cases, the placement of Hostile Architecture in public spaces is seen as a violation of basic human rights, while in other cases it is seen as an effective measure for mitigating crime or improving public health.

Given the controversy surrounding hostile architecture, many organizations are engaging in a dialog about the most appropriate solutions for addressing public safety concerns. In the absence of legal restrictions, cities and other organizations have begun to employ best practices such as removing or altering Hostile Architecture when its presence is deemed inappropriate or harmful.

Public Perception of Hostile Architecture

The public’s perception of hostile architecture is largely negative. Such architecture is often seen as undemocratic and exclusionary in nature, reinforcing existing power dynamics and eroding public trust in authorities and institutions. Additionally, it is regarded by many as a signal of shrinking public space, as well as a symbol of the government’s control over public life.

The increasing popularity of the term “hostile architecture” within the public sphere signals shifting attitudes concerning the use of physical design elements to control public behavior. As public awareness grows, it is likely that designers and other stakeholders will become increasingly mindful of the potential harms associated with hostile architecture.